Another question I was yet to really, seriously ask myself was just what exactly was my goal from this whole exercise. I’d started off wanting to reclaim some shred of my youth, hoping to take that image in my head of my perfect world back then (note: my world was far from perfect, this was just the rose-coloured lenses through which we view history kicking in) and translate it into a feeling I could experience now.

But just how serious was I about making this a reality?

When I mentioned in my last post about the engines between a 1990 and a 1992 being a straight swap, what I should have considered were the handful of small, incremental changes that Yamaha made throughout the versions.

For example, consider the two images shown below. The first is the promo shot for the 1989, the second the promo shot for the 1990. Putting aside the colour schemes (including the fairings, exhaust, mirrors and wheels), and the fact that the 1990 has a plastic cover over the rear seat, there is to my knowledge only one small difference. Can you spot it?

If you said ‘hey, the front brakes look different’, then ten points to you – you’re well on your way to becoming a full-on FZR600 anorak. This, and something that can’t be seen on the pictures in the form of a slightly wider rear wheel, are the only documented differences I’ve found between the two.

So this got my head going – just how close do you want this thing to be to the all-original 1989?

After some reflection, I decided that I wanted to make it close enough that all but the most severe anorak would not be able to spot the difference. Swapping over the brakes to the ones from an earlier model would not only be overly pedantic, it would also be just plain dumb, given that Yamaha upgraded the brakes in 1990 because the 1989 ones were not strong enough for the bike when ridden in anger.

I also decided that it was more important for it to look like my ’89 than a completely stock ’89, which meant that I could abandon looking for a clean exhaust and a clear windscreen, and instead be ok with the combination I had on mine of a louder, lighter aftermarket pipe, as well as a tinted screen.

The real challenge here was going to be the colour scheme.

As I discussed in earlier posts, the condition of the panels wasn’t evident in the pictures, and to be honest they were pretty rough. The Victorian parts bike had delivered on three of the ones I desperately needed, but that still left me with a banged up nose-cone and side panels.

Given that none of the panels matched, it was necessary to get them resprayed and looking like the ’89 ones.

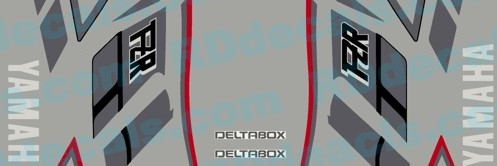

The first challenge here turned out to be easier than expected – sourcing decals. One of the good things about these bikes being more common in the UK/US than here means that there are still places selling decals for them. I managed to get mine from MX decals for around $100 on sale, and I’ve since seen a more comprehensive kit available through RD Decals which includes the frame stickers.

With that sorted, all that was left was to find someone to do the respray. Shouldn’t be too difficult…

It seems, at least in Adelaide, that most spray painters haven’t really engaged with the internet just yet. Searching for spray painters didn’t yield that many results, and nobody who looked like they specialised in this kind of work. I had chatted with the original mechanics who got the bike ready for the roadworthy test about whether they could do it, given that they were primarily a crash repairer, and at a glance they’d said ‘around two grand’, so at least I had a benchmark.

I had a lead on another source who would do it for close to that same mark, but struggled to get in contact with them, so I ended up going to a place that specialised in restoring old vehicles. I had looked at their web presence, and although they specialised in cars, the work they did looked amazing. I should have twigged at this stage what was to come.

I went out to their workshop to get a quote, and I could almost read the guys thoughts as he was walking around it, which I believe were along the lines of ‘this piece of junk looks like a headache on wheels, and if I’m going to quote on this then I’m going to add plenty of risk money into the picture’.

Adding in cost for risk when quoting is nothing new, heck I’d done it before, particularly for small stuff that is likely to end up just being an annoyance and distract you from doing the big stuff that would bring in much bigger income.

With lots of humming and haaring as he walked around the bike, he pointed out all the things that he really wasn’t sure how would turn out – a stress fracture here, a scuff there, the weird shape of the ram air intakes that looked like they would be a pain – along with an admission that they didn’t really do much in the way of bikes…

We both knew by the end of the conversation that we’d not be going ahead with any work on the FZR, and the estimate of $6000 to do the work (no, I’m not kidding, six grand) sealed the end of our relationship. I suspect that on the kinds of cars they restored six grand would have been a drop in the ocean, but this was a beat up old Yamaha, not a 1940s hot rod.

This left me in a bit of a limbo.

I had one supplier with a wildly expensive quote, one who didn’t return calls and one who had demonstrated that their creative thinking skills weren’t all that great, which wasn’t what I really wanted either (although they were, at that point, the best of a bad lot).

This is a good point to talk about return on investment too.

Old vehicles are money pits, and anyone who has sunk way too much money into one will know what I’m talking about. To put my money pit into perspective, I had paid $1900 for it, and let’s pretend I didn’t have to pay for shipping just to lessen the pain. The handful of good condition, twin headlight 89/90 models I’ve seen for sale in Australia have been advertised for around the $3500 mark, and at least at that price they have sold quickly in all cases. That means that a two grand respray alone is well into the realm of over-capitalisation, and that’s not taking into account all the other work that needed to be done on it. Even writing off some of those jobs as ‘running costs’ like with any other vehicle, sinking two grand into paint was really starting to make me question whether it was all worth it. I contemplated leaving it looking like it did, or putting the new motor in and converting it to a track bike (like so many other FZRs ended up), I even wondered how much money I’d lose if I just cut my losses and sold it as it was.

It was at this stage that I got some more excellent advice from Gerard from The Motorcycle Society.

‘Just ride it around for now, while the weather is still good. When we get closer to winter, take it off the road, plan out the project and think about it then. Just enjoy it for now.’

Wise words, even if part of me thought this was akin to being encouraged to spend what little time I might have left with a terminally ill loved one.

Whatever the case, I did just that – forgot about paint, swapping engines and anything else related to fixing it up, and just spent the rest of the warmer months taking it out every week, enjoying the mere fact that it was alive, and that I was with it.

Next up: Using Agile tools to eat the elephant