In the first post of this trilogy I set the scene around the creation of a new student service centre, and noted that many of the enquiries answered during our first ‘peak’ period at the start of Semester 1 could have been very easily done by students online. The question I posed at the end was which enquiries could have we avoided by having them done online via self-service, and how could we have achieved that?

Before I get into proposing answers to that question I want to consider another one – why should we drive enquiries online in the first place?

There are three distinct answers to this question from my perspective. The first two are common across most if not all service centres – cost and customer satisfaction. The cost of scaling out a larger team to meet higher demand (both the direct salary costs and indirect costs such as training, team leadership and knowledge management to support a larger group) is in most cases going to be far higher than the short term investment in moving at least simple services online. Add to this the customer satisfaction improvements for customers who have an expectation of being able to transact online at any time of the day or night, and the case for moving services online is clear in any service centre environment. There is a third however which I believe is far more specific to the Higher Education sector, and which will be the subject of my third and final post of this series…

There are three distinct answers to this question from my perspective. The first two are common across most if not all service centres – cost and customer satisfaction. The cost of scaling out a larger team to meet higher demand (both the direct salary costs and indirect costs such as training, team leadership and knowledge management to support a larger group) is in most cases going to be far higher than the short term investment in moving at least simple services online. Add to this the customer satisfaction improvements for customers who have an expectation of being able to transact online at any time of the day or night, and the case for moving services online is clear in any service centre environment. There is a third however which I believe is far more specific to the Higher Education sector, and which will be the subject of my third and final post of this series…

…but back to the question at hand.

The dimensions of student support

In the first post, I hinted at the number of enquiries that we had that could have easily been done online. These enquiries were the simple ‘transactional’ ones – enquiries that required little or no interpretation or problem solving, and that were ideally suited to being done online in a self-service environment. Some examples of these low complexity tasks include:

- I need to buy a parking permit.

- I need to print a student ID card.

- I need to pay my fees.

- I need to know where South Theatre 2 is.

On the other end of the complexity scale are the enquiries which require interpretation of University policy and the provision of advice to a student which couldn’t easily be done online. Some examples of these high complexity tasks include:

- I need help interpreting course rules so I can select subjects that will let me complete my degree.

- I need advice on what payment options there are for my fees if I can’t pay them on time.

- I need information on what to do if I am thinking of changing my degree.

- I need to resolve a timetable clash I have between two of my classes.

So with this in mind, the challenge then is to make sure all low complexity tasks are done online, right?

Not quite.

There is a second variable in this equation which is somewhat harder to measure, but from what I saw in my temporary role of concierge is just as important to take into account – the capability of the student.

While I spoke to plenty of seemingly very competent students who came in person to perform low complexity tasks (usually for no clear reason other than ‘well I’m here now, so I might as well’), I also spoke to plenty of students who were clearly in need of a helping hand to get them started with even the basics. The most apparent group in this category were international students, who in many cases were suffering the triple-whammy of being new to the country (several I met had come straight from the airport with suitcases still in hand), having English as a second (or perhaps third, fourth, fifth) language, and being new to University life. It wasn’t just international students though – first in family students who hadn’t the first clue of University life (like I was 25-odd years ago), students coming from rural/remote areas, students with some form of cognitive difficulty or students who were just struggling to understand the process of how to commence their studies. Whatever the reason, I spoke with many students who needed a far higher level of support to get the first set of hurdles out of the way so that they could get on with the real reason they came to University – to study in their chosen field.

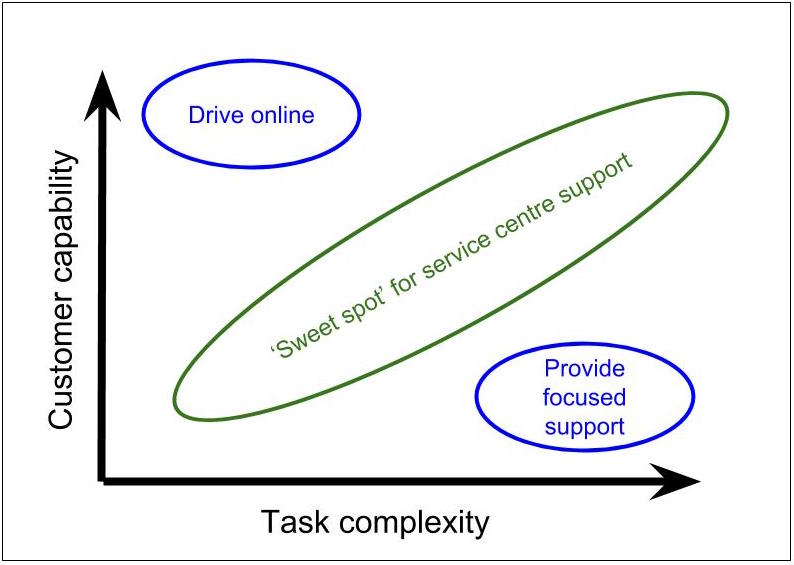

This then gives us a two dimensional model covering task complexity and customer capability. Within these two dimensions, the primary goal of a student support centre like Flinders Connect is to maximise the overall value of the service to students across this spectrum, and to do so in a context of the continual budget pressures of a competitive Higher Education market.

Managing the complexity/capability spectrum

When considering the maximisation of value of services to students across the two dimensions mentioned above, the challenge (I believe) sits primarily in two corners of the matrix, namely:

- Highly capable students accessing low complexity services; and

- Struggling students accessing highly complex services.

The first challenge is moving as much of the low complexity traffic online as possible for students who are able to self-serve. The methods for doing this are a blog post in themselves, but include things like ensuring that the online service meets or exceeds the functions that can be done in person, promoting online methods as the quickest and simplest way to transact, and offering incentives for transacting online.

The second challenge is to ensure that more focused support programs are in place for struggling students who are attempting to navigate more complex tasks in more of a ‘case management’ model. The generalist nature of a service centre like Flinders Connect and its need to accommodate large volumes of enquiries often means that delivery of highly specialised services may not be feasible within the same model, even if the support services need to work in harmony to identify and support students in this quadrant.

The remainder of the demand (shown as the ‘sweet spot’ above) is likely to deliver the highest overall value from a student services team like Flinders Connect: promoting the more capable students to self-serve wherever possible, supporting a wide spectrum of students across all tasks who need a bit of help, and ensuring that more tailored, individualised support services are provided to those students who need them the most to get off to a good start.

So that’s case closed, right?

Not quite. What I’ve discussed above is, I’ve no doubt, generic to any service centre environment – I’m just a bit late to the party to work this out. What I want to discuss in the final post in this trilogy is the unique role which a service centre can, and perhaps should, play in a Higher Education context.