Its been a while since I blogged, which is predominantly due to two factors. One – its been a busy twelve months, and to be honest a fairly rocky one. Two – my focus has shifted from what I’ve traditionally blogged about as my role has shifted into heading up the Consulting team for NetSpot & Blackboard in Australia, New Zealand and beyond.

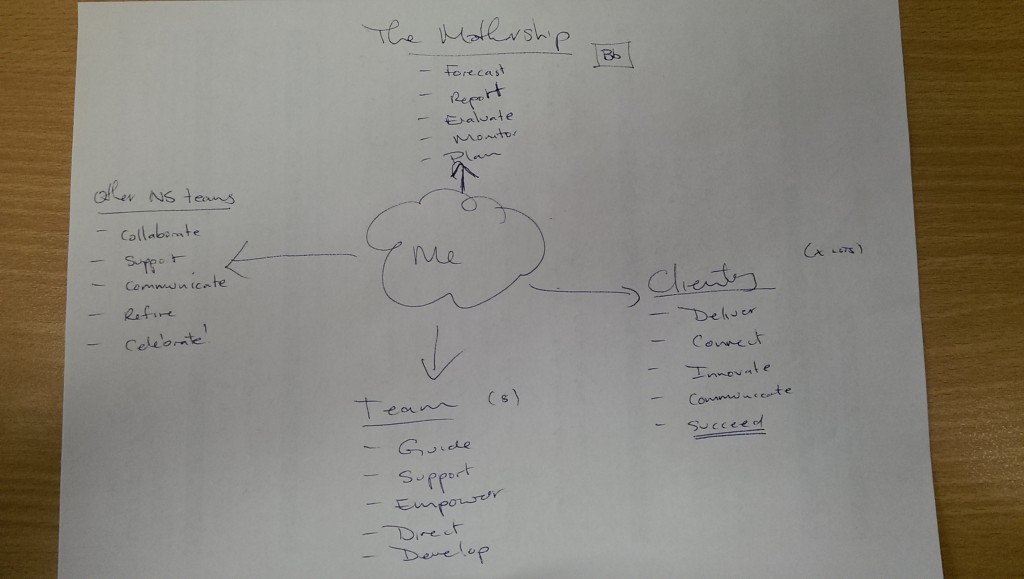

The last year or so of doing very little client-facing work as I’ve moved towards purely leading a team, and some of the challenges we’ve faced, combined with reflecting back on previous leadership roles, made me reflect a couple of weeks back on my main stakeholder groups that I need to regularly devote time to in order to do a good job. I made a quick sketch of my ‘management compass’, and tweeted it to see what people said. It looked like this:

My current hypothesis is that unless I can pay a suitable amount of attention – and respect – to each of those four points in the compass, I’ll fail. Sure, each point might need more or less focus at certain times, but I need to manage them in a considered and balanced way if I want to be successful in this role.

But what if I don’t?

Periods of time when I have neglected one or the other of these led me to thinking about the consequences of not paying due respect to any one of these stakeholder groups, and in the following list I’ve attempted to briefly describe what I think happens when a stakeholder group or ‘point on the compass’ is ignored for an extended period of time. See if any of these leadership types ring true.

Ignoring the boss

The renegade – you act in everyone’s interest except the businesses, or at least the formal representation of the business (i.e. your boss, or the Management team). You know better than them, and you march to the tune of your own drum. Your team loves you, clients love you, most people around the business love you, and maybe you’re even right in your beliefs and The Man is wrong.

It won’t matter.

The machine does not want your type, and like it or not, as a wise man once told me, ‘you have to be big enough to buck the system before you can successfully buck the system’. Goes without saying that the machine is geared to get your type ejected like a virus as quickly as possible – and probably with good reason, as nobody is bigger than the game. Go start your own business – it will suit you better.

Ignoring your team

The absent boss – you let your team ‘self manage’, which is code for ‘you’re never there, and even when you are you have no idea what most of them are up to most of the time’. Maybe you’ll get lucky. Maybe you’ll have a team of self-directed, autonomous superstars, but if you do then more than likely this has been the result of someone else’s hard work (including the team members themselves) to get to this point of awesomeness. Unfortunately for you, over time, as staff change, this self-direction will erode unless you proactively engender it within the new team members (which you’re not doing, since you’re the absent boss).

There’s also the gap between organisational strategy and the goals of the team and its people which you’ll gradually widen for as long as you remain absent, ultimately ending up with a ‘drifting’ team that will ultimately disconnect from the rest of the company, unless you have a superstar in the team who ends up doing your job – in which case they might end up with it permanently when management realise you’re not a leader’s rear end…

And of course if you’re not blessed with a stable, self-managing team in the first place (and let’s face it, how many of us are) – you’re toast.

Ignoring your clients

The corporate droid? – you really don’t spend much time at all thinking about or interacting with your clients, but is this necessarily a bad thing? This is an interesting one, as in some situations you can probably get away with this, particularly if you’re in scenario where things are running well and you’ve got a team (or other teams) engaging with clients well. Perhaps focusing on getting your team to perform is enough to keep clients satisfied. Perhaps you work in an environment sufficiently uncomplicated that the vision for the future of your team is without the twists and turns that come as part of a volatile or complex environment. This is, of course, the best case scenario.

The worst case is that you don’t give a toss about your clients and you are in a role when you really need their partnership, trust, respect and guidance to help you keep your business aligned with what clients need, in which case you might as well quit now – you won’t last.

Let’s go back to the best case though, and you are working in an environment where clients don’t tend to need your attention very often. At least two things can go horribly wrong here though:

- You follow this philosophy during ‘rough times’ when clients above all else need to be reassured that there is leadership within a team helping to navigate tricky waters. If this is the case, and you’re AWOL while the ship is taking on water, you’ll lose the trust of clients quickly, and whatever trust you lose takes ten times as long to get back, just like in any other relationship.

- You are operating in an uncertain or volatile environment (and let’s face it, lots of them are) where being isolated from your clients leads to a significant risk of losing touch with how your clients want your business to evolve over time as their needs change.

In either of these cases, you’re taking a huge risk, and one day it will come unstuck.

Ignoring your peer teams

The protectionist – your vision for success revolves around keeping your clients and your boss happy, and ‘protecting’ your team so that they can do your job. As for other parts of the organisation? That’s their problem, not yours, and if you need to tread on a few toes in order to make sure you get a positive return for your three stakeholder groups then hey – that’s business.

There’s a problem with this though, in that there aren’t too many places I know of that run completely as silos – the performance of The Machine depends on the parts all working in harmony. Machiavelli would have argued that it is better to have people fear you than love you, for love is far more easily overturned than fear, but I’m not convinced that this holds true in any environment where collaboration between teams is essential for the long-term success of a business. First up, while other teams might be obligated to provide you with a service as part of the business function, they sure as heck won’t be going out of their way to help you, and should the worm ever turn and you’re the one in a position of vulnerability, don’t expect people to be running to your side to throw their weight behind you.

In short – you’ll get away with this kind of leadership for a while, but eventually it will catch up, and when it does, odds are it won’t be pretty.

Wrapping up

This isn’t an exhaustive list, nor is it an exhaustive stakeholder model, but it is a starting point for my own reflection, and I’m using it actively as I look at where I’m focusing my time on a weekly basis. I’d be keen to hear anyone’s thoughts (good, bad or otherwise) on the model.

Mark

Perhaps you should think three-dimensionally and add a ‘Z’ axis to your diagram which charts personal health (physical, mental, situational) and introspection and make sure this gets the attention it deserves along with the other points on your compass.

Allan.

Allan,

Agree that ‘ignoring yourself’ could/should get weaved in there, but that perhaps then infers that the machine has an inherent interest in me being personally fulfilled in order to meet its goals. If I ignore the self, then the self eventually burns out, but does this occur on a timescale which is of concern to the machine? Definitely worth pondering.

D

I agree strongly with Allan that there’s a different dimension needed to figure out how good leadership includes practices of self-care. When leaders and managers do it (and often they do) they send a strong message to all their other stakeholders, and self-care becomes a thinkable part of the whole system’s productivity, not its enemy.

But the question I’ve hopped on to ask is about your characterisation of your relationship to the mothership as renegade or footsoldier. I feel that many managers are lured into this unhelpful binary by management training that focuses on the “difficult people” myth. So when you go to a workshop on “dealing with difficult people”, you come away believing in difficult people, and the idea that the best thing to do is “deal with them”, like a waste problem or a server crash.

What if we said “people who have difficulty with you” (obviously not so snappy) and saw them as potentially valuable? What if the workshop was called “Engaging With People Who Have Difficulty With You”? All of a sudden this key stakeholder interaction becomes one that’s full of useful potential.

There’s a great paper about the value of good work in complex organisations which maps out ways of thinking of those who are at odds with the strategic direction of the institution as being capable and useful contributors to improving it. That approach is really helpful, I think.

Kate,

You’re absolutely right, and my model (as many models are) is a gross oversimplification of something that is very nuanced. In my ‘renegade’ tag I was more characterising someone who completely ignores the ‘management’ in a situation as a stakeholder. This is very different to constructively showing ‘upwards dissent’ in order to test a strategy, policy or a low level request for action in terms of it being the best way to go about things. I’ve been very lucky to have Allan as a leader who encouraged this, but was also ready to tell me to suck it up and get on with it if that was the final decision, and early indications are that my new managers within Blackboard follow a similar philosophy, which is brilliant (and I realise how lucky I am in this case). I do my best to promote this mentality within my team as well, that they should absolutely challenge me if they believe we are on a bad path, but I also expect that if I have to make a final call that doesn’t go their way that they’ll get on with it. Being a renegade – to me – isn’t about not being able to challenge a management decision, its completely disregarding it and acting to the contrary, which isn’t a sustainable situation. Big difference I think.

In terms of ‘difficult people’, I try to put a lot of effort into understanding the drivers behind ‘difficult’ behaviour, which a lot of the time are to do with the culture of the organisation, sometimes a flow on effect of pressure within an organisation (which you sum up so beautifully in some of your posts), sometimes about expectation management, sometimes because we’ve simply not done a good enough job, and sometimes (I suspect) because people are occasionally just not pleasant human beings to interact with.

There’s probably a consultancy business waiting to be set up by someone with the appropriate skills you’re alluding to in your comment around relationship management…

Thanks for the comment 🙂